The sales of hydrogen fuel cell cars have largely stalled from 2021 onwards, but does this mean there is no market for fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) in the future, and what is required to make them a success? IDTechEx’s report, “Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles 2024-2044: Markets, Technologies, and Forecasts”, is skeptical about the validity of FCEVs becoming a mass market solution but still sees a limited opportunity under certain circumstances and for targeted applications. Thanks to the very small market now, this results in over 60-fold growth for FCEVs over the next 20 years.

The Problems with FCEVs

FCEVs make very little sense in the automotive market from both a physics and consumer standpoint.

The big advantage for FCEVs over battery electric vehicles (BEVs) is the increased potential range. However, most BEV models can meet the regular range requirements of the majority of people, and for longer journeys, the public charging network is constantly improving. While there is a valid argument that not everyone has access to home charging, this situation is steadily improving, and the same argument can be made for FCEVs; very few stations are in operation, making refueling difficult.

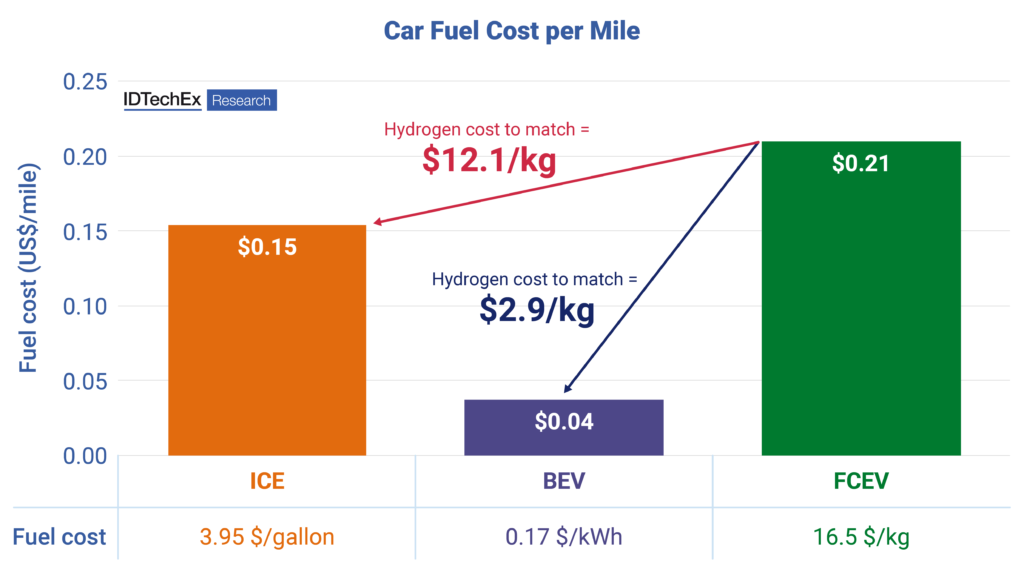

Hydrogen fuel is also very expensive. Using IDTechEx estimates for the approximate costs of diesel, electricity, and hydrogen in California in 2023, a Tesla Model 3 could cost around US$0.04/mile to run in comparison to a Toyota Mirai at US$0.21/mile, which is even above a gasoline/petrol car at US$0.15/mile. While this will vary by region, hydrogen cost needs to be nearer US$3/kg to compete with BEVs.

The vehicles are also expensive to purchase, with a starting price in the US starting around US$50,000 with a Tesla Model 3 starting around US$40,000 (both before incentives). The price of FCEVs has dropped significantly, but the complexity of the drivetrain is a major cause of the increased cost. Compared to a BEV drivetrain requires a battery, motor, and power electronics, a FCEV requires a (much smaller) battery, motor, power electronics, fuel cell, and hydrogen storage.

Efficiency across energy generation is also a concern. Green hydrogen (generated from renewables) will be required to make FCEVs a zero-emission solution. However, if that renewable energy was used for a BEV, then around 75% of it makes it to wheels. For an FCEV, only around 25% makes it to the wheels. Therefore, from a basic physics perspective, when possible a BEV should be used.

What is Needed for FCEV Success?

Subsidies and support schemes have largely driven any success FCEVs have had to date. While this was also true for BEVs initially, the subsidies for BEVs have been reduced dramatically in many regions, but demand continues to increase. FCEVs have been offered with large upfront cost incentives as well as subsidized fuel. In the long term, FCEVs will need to show a compelling ownership argument regardless of financial support from OEMs or governments.

In the short term, governments will need to support the development of a hydrogen economy. Some regions are much more aggressive on this than others. There are more effective uses for green hydrogen than as a vehicle fuel, such as decarbonizing industries where it is conventionally used, including refining and the production of ammonia and methanol or steelmaking, where hydrogen can serve as a reducing gas to produce direct reduced iron (DRI). If these developments can bring the cost of green hydrogen down enough, then it could start to be valid for use in certain vehicles. IDTechEx does not predict that fueling infrastructure for hydrogen will become comparable with existing gasoline/diesel infrastructure, but that in specific use cases, hydrogen stations can be implemented where there is a demand.

Where Should FCEVs be Used?

IDTechEx believes that FCEVs are not optimal for use in vehicles like cars, vans, or buses, where BEVs can largely meet the required duty cycle. Where FCEVs could be used is where the duty cycle is so demanding that BEVs will struggle to cope, and the route is either based at or travels between two hubs using green hydrogen for the applications mentioned above (not vehicular).

IDTechEx has spoken to several truck OEMs and found that many believe there will be long-haul heavy-duty truck routes and climates that, even if megawatt charging is deployed, will struggle to be met with BEVs. In this case, if the fuel is cheap enough, and the region is pushing for a hydrogen economy, then there could be a use case for FCEVs.