With growing lower production costs, rising concerns about climate change, evolving global energy policies, and increasing investor pressure on companies to adopt environmental-social governance (ESG) are pushing renewable energy into the mainstream. As stated by many reports by 2024, nearly 33 percent of the world’s electricity is expected to come from renewables, with nearly 60 percent (or at least 697 gigawatts) of the expected growth coming from solar photovoltaics (PV), according to the International Energy Agency’s Renewables 2019 report released in November 2019. It is followed by onshore wind (309 GW), hydropower (121 GW), offshore wind (43 GW) and bioenergy (41 GW). With American coal-mines are known to have filed bankruptcy in these few years on the other hand, in Australia, the national electricity market showed that renewables reached a milestone powering 50 percent of the country’s main electricity grid. Rooftop solar accounted for nearly 24 percent, followed by wind (about 16 percent), large solar (about 9 percent) and hydro (about 2 percent). Talking about India, a new model of economic development is pioneering across the indigenous renewable sector. India today has also reached as a leader in the energy transition making a remarkable progress in providing electricity while implementing a series of energy market reforms. The revolution in the electricity-generation sector has been seen due to consolidating a high percentage of renewable energy sources into the grid. India is also known to have taken the crown as the world’s largest renewable energy expansion programmes, and this transition to clean energy represents a tremendous economic opportunity for the country.

India’s Renewable Funding

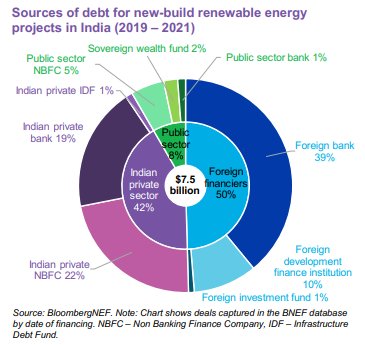

Financing for Indian renewable energy projects comes from a variety of sources. Lenders evaluate several factors, such as the counterparty on acceptance and the borrower’s track record. Refinancing’s are increasingly common. Patient capital providers such as pension funds are also increasingly participating in Indian renewable energy projects.

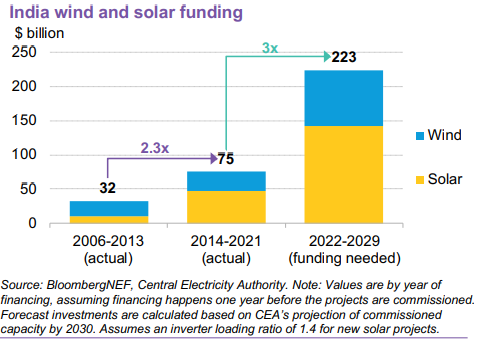

Environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors are increasingly becoming the focus of investors. Project developers are beginning to face higher ESG disclosure standards than government regulations require. Renewable energy developers face regulatory, project, and financial risks. In a survey of 17 industry stakeholders, requests to renegotiate power purchase agreements, land acquisition difficulties, and payment delays were cited as the top risks. Rising interest rates and inflation combined with the rupee’s depreciation against the U.S. dollar are creating new challenges. Regulatory adjustments to banking laws, earmarked clean energy funds, and liberalized commercial borrowing rules could help mitigate these challenges. India is one of the largest renewable energy markets in the world, and its growing demand for electricity combined with government support for clean energy makes it the most attractive renewable energy investment destination among emerging markets. The country now needs to expand its financing activity by tapping alternative sources of finance and learning from international experience to raise $223 billion over the next eight years.

Debt Financing in India’s Renewable Crown

In FY 2021-22, Indian renewable sector received FDI worth $1.6 billion, and further saw year-on-year increase of 269% in FDI from $257.09 million in Q1 FY 2021-22 to $949.45 million in Q1 FY 2022-23. Moreover, between April 2010 to June 2022, the cumulative FDI in Indian renewable sector stood at $11.75 Billion.

IPPs have secured loans from a variety of institutions, with international donors providing 50% of the total amount pursued between 2019 and 2021.

Green renewable energy bonds hit a new high in 2021 as more IPPs turn to bonds to refinance portfolios of commissioned projects.

The report, “Financing India’s 2030 Renewables Ambition”, published in collaboration with the Power Foundation of India, finds that India could achieve 86% of its 2030 target of 500 GW of cumulative non-fossil power generation capacity through the engagement of Indian companies. The report examines the challenges of financing renewable energy, identifies new or underutilized sources of capital, and outlines measures to improve the availability of finance.

India has a massive 450 GW RE capacity target for 2030. Therefore, mobilising funding on this scale will be challenging for two reasons. First, the largest current source of funding, the Indian banking system, simply does not have more capital to lend. The system has long been structurally fragile, was hit hard by the Covid 19 recession, and is approaching regulated lending limits for the energy sector. Second, RE investments are fraught with complexity and risk. Long project delays are common, and power purchase agreements (PPAs) do not provide inflation protection. The main power purchasers — the state-owned distribution companies (DisComs) —are on average 11 months behind in their payments. The DisComs have spooked investors by cancelling signed 25-year PPAs worth billions of dollars. Contract risks are exacerbated by India’s weak and glacially slow legal system.

Most loans in India consist of a limited amount of recourse. Pure project finance without recourse rights is still uncommon in India. Most lenders require some type of guarantee. Smaller IPPs without strong financial backing use right-of-recourse loans, with lenders requiring first right to the assets if the IPP defaults on its obligations.

● Most wind and solar projects in India receive loans of about 15 years. Banks calculate their numbers based on 25-year cash flow projections, but the legal life of the loan is shorter.

There are two other reasons for the lack of popularity of long-maturity loans:

– Tying up $-debt for 20 years is expensive because there are no affordable long-term currency hedges.

– Domestic banks would suffer from an asset-liability mismatch if they made 20-year loans, since the bank’s loans are typically for less than 5 years.

● Development finance institutions such as the Asian

Development Bank (ADB) and International Finance Corp

(IFC) also offer 20-year loans. These usually do not have a repayment option, but there is an interest rate adjustment clause. This means that the loan terms, including the interest rate, can be changed, but the borrower cannot demand early repayment.

● Specialized domestic lenders for the energy sector, Power

Finance Corp. and REC (formerly Rural Electrification Corp.), offered loans with clauses for repayment after 10 years, but this does not appear to be the case now.

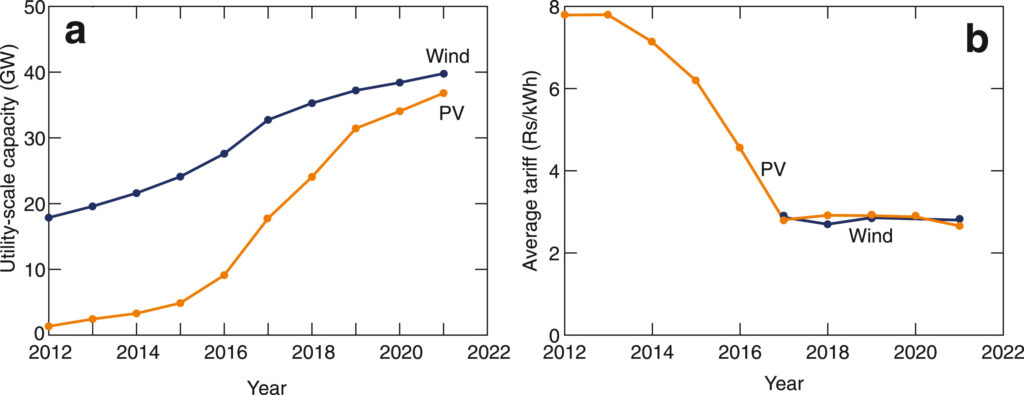

The Market of Renewables in India

As of October 2022, the installed renewable energy capacity (including hydropower) in India was 165.94 GW, representing 40.6% of the total installed electricity capacity. The country is targeting about 450 gigawatts (GW) of installed renewable energy capacity by 2030, of which about 280 GW (over 60%) is expected to be solar. Non-hydro renewable additions were 4.2 GW in the first three months of FY23, compared to 2.6 GW in the first three months of FY22.

Installed solar capacity has increased more than sixteen-fold from 2.63 GW in March 2014 to 49.3 GW at the end of 2021. In 2022, through November, India has added 12 GW of solar power capacity.

Non-hydro renewable power generation was 16.18 billion units (BU) in September 2022, up from 14.49 BU in September 2021. With a potential capacity of 363 GW and policies focused on the renewable energy sector, North India is expected to become the hub for renewable energy in India.

India’s distribution grid is managed primarily (95%) by state-owned DisComs. The DisComs purchase electricity from generators and have a monopoly on distribution at regulated rates. In addition, there are eight private utilities that serve primarily urban areas (including Delhi, Mumbai, and Kolkata). In the following, we focus on the state-owned DisComs.

The DisComs are chronically in financial distress. We devote Section 3 to a detailed description of their plight. All stakeholders of RE need to thoroughly understand the dire situation of the DisComs for the following three reasons. First, the DisComs are the main customers of the power generators. Second, the DisComs are the sole interface with end-users and thus the cash register for the entire power sector. Third, the distribution companies are critical to the regulations governing distributed RE projects. The continued financial distress of the distribution companies threatens the viability of the entire power sector, poses a major buyer risk to RE investments, and hinders the growth of the distributed RE market.

The Government Sector

The 2023-24 budget identifies green growth as one of the SAPTARISHI (seven priorities) nodes. In the 2023-24 budget, pumped storage projects are funded, with a detailed framework to be formulated. The 2023-24 budget announced $1.02 billion (Rs. 8,300 million) in central support for ISTS infrastructure for 13 GW of renewable energy from Ladakh. On November 19, Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurated the 600 MW Kameng hydropower project in Arunachal Pradesh. The project, more than 80 kilometres long and costing about Rs. 8,200 crore (US$1 billion), is located in Arunachal Pradesh’s West Kameng district. On Nov. 9, Finance and Corporate Affairs Minister Nirmala Sitharaman approved the final framework for government green bonds in India. The objectives of the Paris Agreement (Nationally Determined Contribution, NDC) will be further strengthened through this approval, which will also help attract foreign and domestic capital for green projects. In the Union Budget 2022-23, funding of Rs. 1,000 million ($132 million) has been allocated for the Solar Energy Corporation of India (SECI), which is currently responsible for developing the entire renewable energy sector. In the budget, the government allocated Rs. 19,500 crore (US$2.57 billion) for a PLI programme to promote the manufacture of high-efficiency solar modules. In February 2022, Nepal and India agreed to form a joint hydropower development committee to explore the possibility of viable hydropower projects. The Government of India has announced plans to implement a US$ 238 million National Mission on advanced ultra-supercritical technologies for cleaner coal utilisation. Indian Railways is taking increased efforts through sustained energy efficient measures and maximum use of clean fuel to cut down emission level by 33% by 2030.

![SMART ENERGY WEEK [September] 2025 to Lead Global Renewable Energy Advancements SMART ENERGY WEEK](https://timestech.in/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Untitled-design-2025-07-31T112230.406-218x150.jpg)