The sustainability, design, and recovery of electric vehicle (EV) batteries are set to be overhauled thanks to the approval of the EU Battery’s new EU Battery regulations governing the battery market. In June 2023, parliament approved new regulations that set out battery requirements, including a ‘Battery Passport’ and recovery of certain materials. In recent years, the EV market has been trending towards greater system integration, with technologies like cell-to-body and cell-to-chassis designs that can be harder to dismantle and/or remove from vehicles.

Will this change with the adoption of these new regulations?

The new EU regulations cover the entire life cycle of a battery from the mined materials through to their recycling at end of life. To lessen the impact of initial manufacturing, there are requirements for more recycled content in the batteries but also targets for how much lithium (50% by 2027, 80% by 2031) and cobalt, copper, lead, and nickel (90% by 2027 and 95% by 2031) must be recovered from waste batteries. IDTechEx’s Li-ion Battery Recycling Market research has found that 23.8 million tonnes of Li-ion batteries will be recycled in 2043. Making the battery easy to remove from the vehicle and dismantle into parts could help recyclers in the long term.

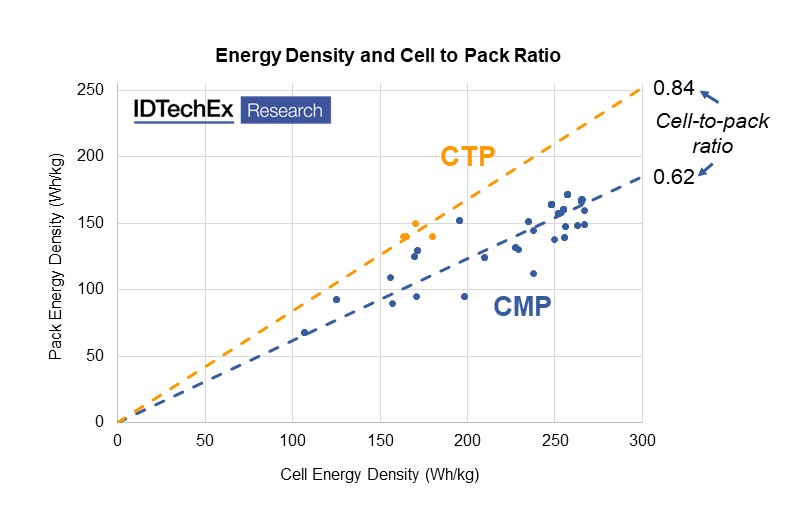

Cell-to-pack batteries are designed such that a battery pack is no longer segmented into several modules. Instead, all of the cells are stacked directly together to reduce unnecessary materials and weight, improve energy density, simplify manufacturing, and reduce costs. Cell-to-body or cell-to-chassis takes this a step further, making the battery pack a structural component of the vehicles structure, again leading to greater integration and reducing the vehicle’s overall weight. The market has been trending in this direction, with manufacturers like BYD already deploying cell-to-pack systems in large numbers and cell-to-chassis designs becoming more common from the likes of Tesla with its 4680 pack.

Initially, one might expect a cell-to-pack design to be easier to dismantle to the cell level, given that there are less overall parts in the pack. However, cell-to-pack designs typically make much greater use of structural adhesives or encapsulating foams that can often make dismantling a pack very difficult, and the standard approach in the event of a fault would be to replace the battery pack entirely. If the adhesives or encapsulants used can be dissolved with a solvent without damaging the cells too much, then this could make recycling much simpler and be a viable differentiation point for material suppliers. With cell-to-chassis, removal of the pack from the vehicle can become a more arduous task, making a recycler’s job much more difficult.

Critically for battery designers, the EU Battery regulations do not state anything about the internal structure of the battery pack (module structure, cell separators, adhesives, etc.). One method of recycling is to crush/grind the battery. This is then sieved to separate larger from smaller particles, with the latter containing the valuable electrode materials. The black mass is then further processed using hydrometallurgy to recover the lithium, cobalt, nickel, etc., in the form of battery-grade metal salts. Ideally, this process would start with just the cells so that the resulting black mass has a higher % of the critical metals. Some have placed entire modules into the grinder; one could also process an entire pack, in which case, the design of the battery means little at end of life, and the designer could take the short-term benefits of a lower cost and easier-to-manufacture battery pack. However, this will make the later stages of extraction more difficult.

In addition to recycling, there is also the opportunity for EV batteries to be used in second-life applications, for example, as stationary energy storage. This bypasses the need in the short term to recycle a battery, and most second-life battery players are currently opting to integrate batteries at pack-level to avoid complex and timely disassembly to cell-level procedures. There would still be a requirement to remove the pack from the vehicle. If the pack forms a structural part of the vehicle, then this would increase disassembly times, making second-life repurposing a more expensive process. However, if a remanufacturer were to hypothetically disassemble to cell-level to make use of the best-performing cells in their second-life battery, a cell-to-pack design (which is not cell-to-chassis) could decrease disassembly times and reduce remanufacturing costs, at the benefit of a better performing second-life system.

In summary, it is unlikely that cell-to-pack designs are going away. If anything, the trend of greater vehicle integration will likely continue, thanks to the reduced manufacturing costs and higher energy density. EV battery packs are generally lasting longer than many initially expected, but in the future, once more EV packs start to hit end of life, the difficulty and effort of recycling large quantities of highly integrated battery packs may become apparent, and designers may have to consider this more carefully for the future, especially as the targets for recovery of critical materials become more stringent.